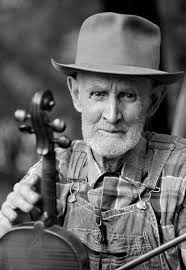

THE LEGENDARY FLOYD RAMSEY

THE APPALACHIAN STRING BAND FESTIVAL “GLUE”

Some say “home” is where your story begins. Down an abandoned road off Route 60 near the ghost town of Winona, WV, sits a humble home near a now defunct coal mine. If you were to step on the porch of this house and politely knock, you surely would be welcomed in.

Once inside the main room of the small frame house, built during the glory days of West Virginia mining, you would find a smiling older man standing under the mounted head of an enormous buck deer with antlers taking up much of the rooms ceiling space. The amazing thing about this mounted buck is that each and every spike of those antlers is draped with a hat or t-shirt. Each of these adornments displays a different year’s logo and commemorations of the Appalachian String Band Festival held annually since 1989 at nearby Camp Washington Carver, in Babcock State Park.

Should you engage the owner of this display, you would quickly learn that you are not dealing with an ordinary mountain dweller, but the unofficial “Mayor” of the annual gathering of musicians from around the world known affectionately as “Clifftop,” and that this man takes that moniker very seriously.

You would also learn that each of those garments has a revealing story behind it, which will be related to you by a master Appalachian storyteller who, since 1992, has dedicated his many skills and his deep love of people to the musical community of two to four thousand who gather for nearly two weeks each summer to play the music of the mountains.

Although Floyd Ramsey retired several years ago from his official job, the real exact title of which is always in dispute, he can’t stop spending his year preparing for and greeting the thousands of travelers who come from around the region and across the world to participate in the West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture, and History’s Appalachian String Band Music Festival each year.

Over the years Floyd’s job has been referred to by others and West Virginia’s State website as Camp Washington Carver’s “Assistant to the Director,” “Head of Maintenance,” “Building Laborer.” If you ask Floyd himself, the answer is succinct, “maintenance,” he drawls. Most String Band campers would disagree. They respond with descriptions like “rattlesnake wrangler,” “that guy who blows the whistle,” “fix it guy,” “dispute settler,” “that guy who pulls campers out of the mud,” and many more practical titles. In the end, perhaps longtime Clifftop camper and musician Rob Coulter, from rural Craig County Virginia, puts it best, “Floyd is the glue that holds Clifftop together.”

Floyd has done all these things and much more. Born in Winona, “Up on top of Flannigan mountain,” as he puts it, he has lived in Fayette County about six or seven miles from Camp, his entire 70 years. His partner and girlfriend, Jessie, have been together more than 40 years. Together they have raised three boys and been active in the area’s community life. “She told me she didn’t want to ever get married,” said Floyd, “because she was afraid the good thing we have might change.”

Before joining the staff at Camp Washington Carver, Floyd held a variety of jobs locally and for the state. In the 1970’s when the area coal mines were in full operation, he even worked for a year as a coal miner. One of his jobs for the state that he is most proud of is helping to build the Glade Creek Grist Mill in Babcock State Park that Washington-Carver is a part of. Set on top of a boulder strewn stream, the mill is a working replica of Cooper’s Mill that was once located nearby, according to West Virginia Park Service. The mill was pieced together with original parts that were collected from much older mill ruins in the area. Floyd and his coworkers constructed the mill in 1976, and since then it has become the most photographed mill in the U.S and is famous around the world.

“I didn’t know nothing about the festival when I got hired here,” said Floyd, “They just told me it was a music festival. Floyd told his superiors before coming to work at Camp Washington Carver that if he didn’t like what was going on, he wanted to work somewhere else. That never happened.

“From the minute I came here, I loved this old Camp,” Floyd explains, “And then I met the people. I’ve never met better people than the folks who come to camp and play music here,” said Floyd.

Taking care of Camp Washington Carver and getting it ready for the influx of campers each summer has to be a daunting task. Built in the late 1930’s and early ‘40’s, the camp initially served as the state’s first state-wide camp for African American 4H members. It’s cabin-like structures and 90 year old infrastructure requires constant attention. Floyd and his coworkers spend weeks each summer preparing the buildings and grounds for the strain of thousands of musicians using the facility for more than two weeks in late July and August.

Named for West Virginians Booker T. Washington (who worked in the local coal mines) and George Washington Carver, the camp boasts the largest log structure of its kind in the world, Great Chestnut Lodge. It is used for several events throughout each summer including camps, reunions and weddings and is featured on the National Park Service’s African American Heritage Trail, but the String Band Festival is by far its heaviest use.

Each summer Floyd and others mow, groom, and meticulously prepare the large camping grounds by clearing downed trees and limbs, filling in potholes, dealing with rain damage and flooding in the legendary “bottoms” and attempt to relocate snakes, bears, bees, wasps and other wildlife that might not be good camping companions. Then the campers arrive.

One of the discerning features of the camp that has become an icon to participants is the camp’s water tower, located on the highest point on the camp grounds known affectionately to attendees as “Geezer Hill,” named for the propensity of older campers to congregate their campsites there.

Most people assume that the limited water supply comes from that tower, but in reality providing flush toilets, sinks and showers for attendees is much more complex.

“The water is pumped up the mountain from a well that is a mile and a half away, treated, and then held in large underground storage tanks,” said Floyd. “It’s always a battle,” keeping enough water flowing for the number of people we have.” Accordingly, Floyd and the staff have to regulate shower hours and restrict the use of water at times.

Beyond water management and groundskeeping duties, maybe Floyd’s greatest skill is in helping to manage camper behavior. Putting thousands of musicians, their friends and families together for two weeks can create some chaos and require some minimal rule enforcement and that duty has also been part Floyd’s duties.

“When we first met Floyd, back in the first years, we realized he had the ability to help people follow rules without causing too much commotion,” said the festival’s co-founder, musician and original camp host, Will Carter. One of the early Directors decided that each camping area should be clearly laid out, with strict boundaries. He set Floyd to chalking off camping areas and numbering each one. Will didn’t like the idea and argued that “if we treat these folks as adults, they’ll work it out and respect one another.” Floyd whole heartedly agreed and set about erasing all of the boundaries.

Consequently, a broad patchwork of musical communities have evolved. From the top of “Geezer Hill,” to the youthful “bottoms” you’ll find camping clusters of like-minded musicians, gathered by genre, i.e., “Cajun Land,” geography, “Charlottesville” or just silliness, “Moose Camp.” Over the years, Floyd has managed to study, understand, and have friends in each of the more than 50 separate camping communities that have formed, evolved and grown.

That community knowledge has proved invaluable to some campers. One year a young man that everyone knew as just “Fiddler” came to Floyd looking for water and Floyd helped him fill some large jugs and hauled him and the jugs backed to his camp. Later in the week, Floyd was contacted by staff who had received a phone call for someone among the three thousand campers known as “Fiddler.” The caller said that his mother had passed away and they needed him to come home. Astonishingly, Floyd knew exactly where to find him and delivered the important message and was able to pass it along in time for “Fiddler” to make the funeral..

Something that makes Floyd’s referee duties easier, is that for the most part, each group tends to solve its own problems without involving staff. “I remember one year a group had a rough character who was causing problems, and before that day was over I saw them drive that man to the entrance and tell him not to come back,” recalled Floyd, “That’s the way it usually works, they just take care of it.”

.If you asked Floyd about the hardest part of his job over the years he is quite clear. “We’ve had two deaths here,” he’ll tell you, “That’s hard on all of us.” The camp has medical staff, but maneuvering ambulances and responders into the intricate web of campers and dealing with protocols can take hours and weighs heavily on Floyd and the rest of the staff.

Legend has it that Floyd has used whistles, loud airhorns, shutting off lights and lanterns and a variety of other methods to shut down late night jams and dances that have gone on just too long.

In addition, Floyd’s skills as a rattlesnake and bear wrangler have also become part of Clifftop’s lore. The biggest snake that Floyd recalls he had to remove from a camper’s area was a six foot Timber Rattler. Using a snake handling tool, he wrestles the snakes he relocates into gallon buckets with plexiglass tops because so many of the campers from far away are curious. One can find many photos and videos of Floyd’s snake removal on YouTube.

“The music vibrates the ground,” said Floyd, “And the rattlers are attracted to the vibrations.” Thus, even the camp’s wildlife are drawn to Appalachian string band music.

One camper recalled asking Floyd what happens to the snakes he caught. “Well, I can’t kill them, because they are protected,” answered Floyd. Then a familiar twinkle, known to hundreds of campers overtook Floyd’s face as he lied, “I just cut off the rattles and then they can’t bite anybody!” More than a few gullible campers have succumbed to the mountain man’s sense of humor.

Floyd’s role as rule enforcer is clearly balanced against his deep caring for people. He has hauled hundreds of stuck campers out of mud, helped parents find lost children, comforted folks not used to the mountains’ furious storms, removed bears from under campers and settled disputes between camp sites, all with very little expectation except the friendship of the folks he’s helped. Roy Clark, Jr., son of the famous Hee Haw start, for example, was totally stuck one year and told Floyd, “If you can’t get it out with the tractor, just open the windows and let the squirrels move in.” When Floyd got him unstuck Mr. Clark tried to give him money. When Floyd refused, he offered a CD he had recorded instead. “I’ll take that,” said Floyd. In Floyd’s home you’ll find a large stack of old time CDs, right next to the T-Shirts and ballcaps hanging off the buck representing a lot of hard work and a lot of friendships.

With more than 20 years of service to Camp Washington Carver, Floyd retired from the State of West Virginia in 2019 with one condition, that the State would let him come back and work at the String Band Festival every year. 2025 is his sixth post-retirement year greeting Clifftopers, telling stories and helping thousands of musicians have the experience of their lives..

“He has become legendary,” said Will Carter, “Just one name, like Bono, or Madonna, or Elvis.”

Bands have been named after him in Rhode Island and songs have been written about him in Baltimore. One camper from New Hampshire recounted that among younger campers in the “bottoms” stories and cautionary tales are told late at night about Floyd’s antics, passing on tales about rattlesnakes, bears, and rule enforcement..

One thing is for certain. Floyd and The Appalachian String Band Festival at Camp Washington Carver are synonymous. He has become not only the glue that holds the festival together, but part of the folklore that makes the festival beloved by so many. And now, Floyd is joined on the crew, full time, by his oldest son, Kenny, who is learning the ways of Clifftop and Camp Washington Carver. When Kenny was invited to join Floyd and the crew, he hesitantly asked his dad, “What kind of people are these folks, dad.”

“The best people in the world,” replied Floyd. The tradition and the stories will continue…

A Legacy of Music and Family: Uncle Norm

(Photo by Mark V. Sanderford)

A wise family therapist once observed that families who can tell family stories and laugh together are healthy families. Well, if that’s the case, the descendants of Norman (“Uncle Norm”) Edmonds are beyond healthy, they’re well. On a misty early fall evening shortly before Hurricane Helene would wreak havoc on SW Virginia, laughter and stories rocked the rafters of the Laurel Fork Community Center. Gathered together at my invitation were Norm Edmond’s granddaughters Crystal Goad, Brenda Meares, Rita Goad Biggs, and Rhonda Anderson; grandson Ronald Sawyers; and Jennifer Bunn, Norman’s great granddaughter. They were there to share their collective memories of the legendary SW Virginia fiddler affectionately known to everyone as “Uncle Norm.”

It was late September of 2024 and in just a week I was going to host a gathering of musicians on my farm near Laurel Fork and close to where Uncle Norm had lived to celebrate his life and music. The weekend gathering was to include lots of music and community as well as presentations from musicians and family members. Then, just a day before the gathering all Hell broke loose as we endured the very tip of Helene’s wrath. The celebration was cancelled for now, but the stories and laughter of the Edmonds family linger.

Learning to Play

Uncle Norm, whose mischievousness was well known, probably would have relished the thought of a hurricane disrupting our celebration. Born in 1889, to Scots Irish parents who had immigrated to Virginia, Norm was one of four brothers, all of whom took after their father who was a lover of music and a fiddle player. Norman was born in Wythe County, just past the Carroll County line, nine miles from Hillsville in the small community of Patterson. All that remains today of Patterson is a small community center and the 200 year old building that currently houses Carpenter’s Grocery. At the time of Norman’s birth, it had been settled by many immigrants, mostly from Germany, which may explain why Norman’s father spoke German well and Norman knew enough German to later tease his grandchildren with.

His father, John Edmonds, played a homemade gourd fiddle, and from an early age, Norm, the youngest brother, wanted more than anything to learn to play that fiddle. He was so taken with hearing his father and brothers play music that he would do nearly anything to learn. He had the craving and it wasn’t going away. At about the age of five, Norm would wait until his father and older brothers had gone out to work in the fields and then sneak into the closet where the precious fiddle was kept and, carefully imitating everything his father had done, try to scratch out a tune. It didn’t take long for Norm, who like his brothers seemed genetically disposed to musical ability, was playing many of his father’s civil war era fiddle tunes, having kept them in his head. His fingers seemed to fly up and down the neck and he soon mastered the complexities of bowing just by experimentation.

One evening, as the family was gathered in the small parlor of the house, John Edmonds asked his youngest son if he wanted to learn to play and handed him the old gourd fiddle. According to the family, every jaw in the room dropped as young Norman begin to play his father’s repertoire, note for note. It seems that this sneaking about to learn to play is some sort of family tradition among the Edmonds, as two of Norm’s grand-daughters and a great granddaughter related how they had snuck to family instruments and picked them up while their parents weren’t looking. In great granddaughter Jennifer Bunn’s case, it was Uncle Norm’s very fiddle that she snuck out to play and now, years later she plays it regularly. The room at the Laurel Fork shook with laughter and acknowledgement as each of the women disclosed their mischief.

The tunes that the older Edmonds played and taught represented the tunes he had learned from his father, Uncle Norm’s great grandfather, but were now “appalachianized” by the influence of local styles and tunes that his neighbors played and the melodies that made the rounds during the Civil War. As young Norman’s fiddling developed, his tune list reflected nearly 200 years of Appalachian music and like other fiddlers of the region at the time (Tommy Jarrell of Mt. Airy, NC; Henry Reed over in The Narrows, VA; Fulton Myers of Five Forks, VA: and a host of fiddlers in Galax) brought pre-civil war tunes back into the local fiddle repertoire. Norman’s capacity for learning and keeping tunes solely by ear seemed remarkable. Among the tunes young Norman learned from his father were “Walking in the Parlor” (He reportedly loved to play it while Norm’s mother, would be making breakfast for the family and he’d sing it to her “Walking in the parlor/walking in the shade, Walking in the Parlor with a pretty little maid.”

Other tunes that came from Norm’s father John included “Old Aunt Nancy,” “Lucy Neil,” “Ship in the Clouds,” and one of John’s favorites “Hawks and Eagles.” It is speculated that “Hawks and Eagles” was actually a Wythe County tune, passed along in the mid 1800’s. John and later Norman would sing words to it, too:

“Hawks and Eagles, going to the mountain,

Hawks and Eagles going to the mountain.

Hawks and Eagles going to the mountain-

Boys and girls, you better get away.”

John had learned tunes from his father as well as other musicians in Virginia. His earliest fiddle was a cornstalk fiddle, a tradition he taught his children how to make. “You could get a lot noise out of those things,” remarked one of Norman’s sons. As John and his four sons held regular sessions and at least one of Norm’s brothers also played the fiddle, Norman began to clawhammer the banjo and soon became adept at playing it both with his family and other local fiddlers. Norm also taught himself the guitar and the pump organ, so he could play in a variety of situations.

In 1917, at the age of 28, Norman fell in love with Fedella, a beautiful ballad singer who was 16, and they were married and moved to the Willis, VA., area. Norman was sort of a “jack of all trades” and subsistence farmed; growing a garden and keeping livestock, but continuing to get out and play music with friends and neighbors. He and Fedella (often known as “Dean”)were also raising a family of nine children, including six boys and three girls. They made sure that each of their children appreciated music. Playing with their father or singing with their mother and learning to dance was part of the family’s heritage to be preserved and passed on.

Norman and Fedella (or “Dean”)in their later years. (Photo by Mark Sanderford)

The Big Bang

Besides playing music with his family, Uncle Norm continued to seek out local musicians to play with. One of his favorite banjo players was a man from the Laurel Fork area of Carroll County by the name of J.P. Nester (1876-1967) who most folks referred to as “Pres” after his middle name, Preston. Pres played the mountain clawhammer style of the region and was crisp, clear and powerful in his delivery. He also sang well and learned many of the old tunes of the Galax region. By day, he would operate the Hillsville telephone switchboard, and then hike out into the Blue Ridge at least seven miles, to where Uncle Norm was living, and play until midnight. The two became good friends and were in demand. Their style, according to many folklorists such as Charles Wolfe, represented the original fiddle/banjo duet style of the Blue Ridge well. They were asked to play for house parties, school dances and pie suppers around the area.

Reportedly, it was very hard to get Pres to travel out of the area. He didn’t much care for automobiles or trains and preferred the confines of Carroll County, where he could walk without much bother. After playing regularly for a furniture store owner in Hillsville, a once in a lifetime opportunity came along. The furniture man had been approached by an RCA executive from New York, who was setting up a field recording studio in Bristol, TN., 100 miles from Hillsville.With much coaxing, Norm convinced Pres it was worth the money and travel to go down and be recorded by the RCA representative, whose name was Ralph Peer.

In August of 1927, A.P Nester (Nestor) and Norman Edmonds recorded four sides at what is now know as “the Big Bang of Country Music” or simply the “Big Bang.” Among the other musical “discoveries” Peer made during those sessions were soon to become legendary figures in early country music, including The Carter Family, Jimmy Rodgers, The Shelor Family, Blind Alfred Reed, Henry Whitter and a host of others. Uncle Norm’s name was not highlighted on the recordings. They were simply listed as “A.P. Nestor (sic.)” The two musicians recorded four sides for Peer. Two of the recordings were released by RCA later that year: “Train on the Island” and “Black-Eyed Susie.” Norman’s fiddle soars above Pres’s powerful banjo on both cuts forming a nearly perfect example of early string band music from the Blue Ridge.

Two other sides the duo recorded mysteriously disappeared in transit to Peer’s New York office. “John My Lover” and “Georgia,” would never be heard, and purportedly the two remaining tracks would be the only recordings we have of Pres Nester’s playing. To add some insult to the event, Peer misspelled Pres’s last name (“Nestor”) and subsequently every re-release and nearly every historical account of the collaboration between Norman and Pres Nester has wrongfully attributed his playing and singing to “J.P. Nestor.” His and Norman’s rendition of “Train on the Island” remains one of the best examples of old time string band music and has been included in countless anthologies of music and dissertations about the music. When self-proclaimed folklorist Harry Smith released his “Anthology of American Folk Music” years later, he included the tune and the misspelling of Pres’s name. To this day, nearly 100 years later, there are hard feelings in the local area about the misspelling.

J. Preston (Pres) Nester’s grave marker in Cruise Cemetery near Laurel Fork. Correctly spelled.

Currently there are no other “Nestors” in this geographic area, but there is a large population of Nesters. One often told local story recalls that in the early part of the last century an itinerant preacher told the Nester family members that “Nester” had uncouth connotations and they should change their names to the more stately “Nestor.” According to the tale, all of the families that changed their names to Nestor were shunned locally and eventually they relocated to the mountains of West Virginia where the name has flourished. In any account, the lone grave of John Preston Nester, banjo player extraordinaire, rests beautifully on a mountain near Laurel Fork, VA., in a small cematry overlooking the valley of the Big Reed Island Creek, with the correct spelling of his name. Recently, the Museum of the Birthplace of Country Music in Bristol, that is dedicated to preserving the importance of Peer’s recording sessions, has made an attempt to right the wrong done to Pres’s legacy by correcting the spelling in their exhibits and displays.

The Music House

When Uncle Norm moved his family to a home closer to Hillsville, just off Rt. 58, the importance of passing on his musical heritage became a priority for him. With his family’s help he built a one room outbuilding, specifically for family gatherings to play music. They constructed the music house out of cinder blocks, carefully filling each block with straw to add “soundproofing” for both the walls and wooden floor. Uncle Norm wanted to be able to practice and record his music here. Uncle Norm supported his family by doing a variety of jobs including working on the railroad, working at sawmills, building furniture, gardening, playing music and piecemeal work where ever he could find it. On one trip to Indiana, he bought a pump organ and brought it back to the Blue Ridge only to find it was too big for most of the house, except in the bedroom, where it landed and stayed. He would play hymns on it while the family sang from the bed and the hallway outside.

As his children aged and started their own families, it became a tradition for the local family to gather for music on Sundays before church. They would gather in a circle of chairs at 7:30 and play for two hours solid, before joining in a huge breakfast, finished just in time to make it to the 10:00 Presbyterian Church service down the road. His grandchildren all remember these Sunday rehersals as jubilant gatherings with Uncle Norm leading the family in tunes and songs, usually with his small dog, Penney, seated on his lap and looking longingly into Uncle Norm’s beard. Here he and his boys and sometimes grandchildren, played while some of the daughters danced and his wife set the large table in the music house with a Sunday feast.

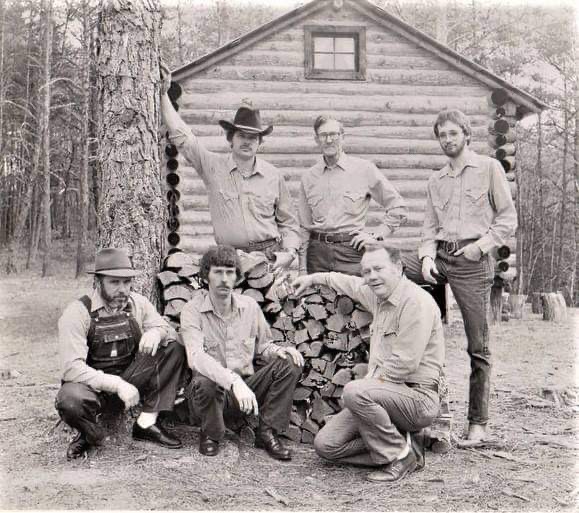

Rufus “Berry” Quesinberry, Uncle Norm, and Paul Edmonds (photo by Alan Lomax)

In the 1950s, a local banjo player named Rufus Quesinberry began to join the family for Sunday practice and became Uncle Norm’s go-to accompanist, along with various configurations of his sons, often including Paul, John, and Cecil on guitars and Nelson on bass. He aptly named this mostly family band, with rotating banjo players, “The Old Timers.” About 1955, Uncle Norm was requested to play for 15 minutes every Saturday morning on a local radio station while the studio announcer shared local grain and hog markets. Norman’s son, Rush, dutifully collected these shows on tape, and they later became the basis for two volumes of recordings released in 2015 by the Field Recorder’s Collective (FRC 301 and 302, 2015). The pleasant banter between the announcer and Uncle Norm makes for great listening, as does Uncle Norm’s playing. The show continued until 1970, when Norm, at the age of 81, hung up his fiddle.

During his 60s and 70s, Uncle Norm’s music career thrived with performances at various fiddler’s gatherings, contests, local dances, and social parties. The onset of the “great folk scare,” brought on by the release of the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, kept interest in Uncle Norm alive among students of Old Time music, and many traveled to hear him play and learn from his vast repertoire of fiddle tunes. One such “folkie” was the great folklorist and field recorder from the Smithsonian, Alan Lomax, who came to Hillsville and recorded Uncle Norm and the Old Timers in August of 1959. He recorded a variety of tunes including “Sally Anne,” “Lonesome Dove,” “Walking in the Parlor,” “Salt River,” “Greasy String,” “Breaking Up Christmas,” and “Bonaparte’s Retreat.” The Old Timers that day consisted of Norman, son Paul on guitar, and Rufus Quesinberry on banjo. (These recordings are accessible at https://archive.culturalequity.org/solr-search/content/list?search_api_fulltext=Norman%20Edmonds)

Lomax’s interest in Norman and the subsequent release of some of the recordings he made brought young people flocking to his door and found his Sunday sessions and breakfast often joined by strangers from as far away as Ireland and England as well as tune seekers from up and down the East Coast. Norm and his family welcomed all comers and he was excited to pass his musical heritage on to a new generation of players.

Although Norm and The Old Timers often played at the famous Galax Old Fiddler’s Gathering, Norm never placed in the individual fiddle contest, but he and The Old Timers placed fourth in the 1964 old-time band contest.In 1970, Uncle Norm was an honored guest at the Galax festival and was asked to play on stage. With a great sense of tongue-in-cheek, he boomed out a version of “Monkey on a String,” and the 81-year-old fiddler brought the crowd to its feet. It was his last public performance.

Legacy

(Photo by Mark V. Sanderford)

As Norman and Fedella moved into their later years, their kids worried about them being so far from town with so much to manage and they built a small comfortable cabin for the folks to live out their remaining days, closer to Hillsville. Uncle Norm passed away in November of 1976. He was 86 years old. Fedella Edmonds lived on until 1992. She died at the age of 92. When I asked the gathered grandchildren and great granddaughter of Uncle Norm what they thought music meant to him, they were unanimous in their response. “Family legacy,” they all agreed.

Much of Norm and Fedella’s later lives involved being active in the lives of their children and especially their grandchildren. All of them remember the music and the gentle teasing their grandpa would give them. Often he would blurt something out in German to startle them or tell a joke and make them laugh. They sometimes would get him back. For example, Norm would hide his “hooch” on top of the refrigerator and sneak it out to the music house to take a snort now and then, being careful not to let the grandkids see it. When the bottle got lower and lower, Uncle Norm, who wasn’t a steady drinker, could not figure out what had happened. He never suspected that his granddaughters were climbing up on chairs to get the bottle and pour some out whenever he wasn’t looking. It was evident that the Edmonds house was filled with love, music, and a deep respect for family and legacy.

Besides the tapes from The Oldtimer’s radio show, preserved by the Field Recorders Collective, only one other album of Norm’s music survives. In 1973, Davis Unlimited Records released “Train on the Island: Traditional Blue Ridge Mountain Fiddle Music.” On the album, Norm and banjoist Rufus Burnett recorded in the classic fiddle/banjo style of the region. Included are newer versions of the two songs that launched Norm’s career; “Train on the Island,” and “Black Eyed Susie,” as well as tunes that Norm has become well known for such as “Ship in the Clouds,” “Lucy Neil,” and his unique version of “Hawks and Eagles.” In the 1990’s due to demand the album was rereleased on CD.

Tragically, in 1998, Uncle Norm’s son, Lewis “Rush” Edmonds died in a house fire. Rush, who had a keen interest in recording technology had recorded years of radio shows and years of family gatherings in the music house that Norm had built and those years of tapes went with him. No other recordings of Norman Edmonds and his beloved Old Timers exist.

Norm’s family legacy carries on among his grandchildren and great grandchildren. Nearly every one of them plays some type of instrument or has a deep appreciation for the music of the mountains. Nelson Edmonds, for example, was one of Norm’s sons that everyone called, “Harry.” Harry not only played a variety of instruments but built guitars and fiddles also. He encouraged his son, aged 5, to sit down next to his Grandpa and learn how to move the sticks like grandpa played the fiddle. After that, he rarely got to play with his cousins at family gatherings because his dad wanted him to fiddle.

Soon, Jimmy was playing so well that he became a fixture at the family gatherings in the music house. By the age of 10, Jimmy was not only playing with his grandpa, but would accompany legendary banjoist Wade Ward on stage as part of the legendary Buck Mountain band from Independence. Jimmy carried the family legacy of music on to win the fiddle category at Galax and many other contests, become a sought after multi-instrumentalist, a producer of the Carolina Opry, and the builder of over 300 high end acoustic guitars. Jimmy also played a fine clawhammer banjo style that he learned from Wade Ward, and one year at Galax took first place in front of Wade who placed second.

Another granddaughter of Uncle Norm’s, Barbara Poole (1950-2008), Jimmy’s sister, learned to play the bass, the mountain dulcimer and to sing. She started her career as a child playing with her brother in the Buck Mountain Band, and later went on to have a career in old time music playing with the likes of Whit Sizemore and the Shady Mountain Ramblers, Richard Bowman and the Slate Mountain Ramblers, banjoist and singer Larry Sigmon, The Toast String Ticklers that included Vernon Clifton, The Grayson Highland Band and others. The family legacy stayed and stays well alive.

Jennifer Bunn, Uncle Norm’s great granddaughter plays his fiddle

Today, Jimmy Edmonds still builds guitars and occasionally can be heard making one of his grandpa’s fiddles sing. Uncle Norm’s great granddaughter, Jennifer Bunn, also has one of Uncle Norm’s fiddles and plays it every chance she gets, having recorded a bluegrass CD and continues to make music in the Presbyterian Church in Hillsville that her great grandparents attended.

Next Fall, we will once again try to gather the scattered Edmonds descendants and Old Time Music fans from across the nation in my back pasture to celebrate the incredible life and legacy of Uncle Norm Edmonds. We will have folklorists, musicians and family members pay tribute to a life and legacy of old time music here in the Blue Ridge. Whatever happens, I know it will be a legacy of music and laughter.

References Used in this Article:

Bekof, J., (2012) J.P. Nester and Norman Edmonds,Old Time Party Blog, retrieved from:https://oldtimeparty.wordpress.com/2012/04/24/j-p-nestor-and-norman-edmond

Donleavy, K., (2004) Strings of Life: Conversations with Old Time Musicians from Virginia and North Carolina, Pocahontas Press, Blacksburg, VA.

Field Recorders Collective, (2015) Uncle Norm Edmond and the Old Timers,, Vols 1 and 2, (2015) 301 and 302, available at: https://fieldrecorder.bandcamp.com/album/frc-301-norman-edmonds-the-old-timers-vol-1-andy-cahan-collection

Smith, M. (2024) Personal Interview with Descendants of Norman Edmonds, September 14.

Wolfe, C.K. & Olsen, T. (Eds) (2005), The Bristol Sessions: Writings About the Big Bang of Country Music, McFarland Press, West Jefferson, NC.

Uncle Wade Ward!

Here is a multimedia piece I created for the Virginia Folklife Program about Wade Ward. Please check out the personal tributes at the end, including playing from Walt Koken, Bruce Molsky, Paul Brown and Mac Traynham! Click Below:

https://www.virginiafolklife.org/sights-sounds/a-tribute-to-virginia-folk-hero-uncle-wade-ward/

Nobody’s Business

A PR piece for one of my favorite local bands

Malcolm Smith

Every once in a while an old time string band becomes the go to dance and entertainment band up on the Blue Ridge. It has happened with such bands as the Dry Hill Draggers, The Cabin Creek Boys, The Whitetop Mountain Band, The Konnarock Critters, the Slate Mountain Band and so on. The latest band attracting hordes of dancers and an army of loyal listeners up in the highlands of Virginia and North Carolina is “Nobody’s Business’

The band’s driving sound is derived both from the genetic rhythm created by master musicians but also from a genuine love of old time and early blue grass music. All of the members of this band trace roots to the Grayson Highlands area of Virginia as well as North Carolina high country. But what really makes “Nobody’s Business” stand out is that the musician’s lives are deeply dedicated to the art of old time mountain music and traditions in many other ways.

Take guitar player and “high lonesome” vocalist, Jackson Cunningham for example. When Jackson is not studying the various guitar styles and perfecting the vocalizations of the region, he is building some of the finest guitars on the planet. Cunningham Stringed Instruments is selling handmade guitars made in Mouth of Wilson, VA. around the world to those seeking an authentic old country sound.

Fiddler and vocalist Trevor McKenzie is a professional music archivist, author, and Director of the Appalachian Studies Center at Appalachian State University. A former apprentice of the great mountain fiddler and banjo player, Paul Brown, Trevor is immersed in Appalachian musical traditions. His most recent book, “Otto Wood: The Outlaw” details the life of an Appalachian bandit who was made famous by a ballad sung by, among others, Doc Watson

Corbin Hayslett, the banjoist, is considered to be a master of a variety of Appalachian and Blue Ridge banjo styles and can adapt his playing to both old time and early blue grass. Besides his playing, Corbin promotes his knowledge and love of mountain music by serving as General Manager of County Sales, the only music store in the nation devoted solely to old time and bluegrass music. In addition, Corbin serves as a mentor and teacher at the renowned Handmade Music School in Floyd, VA.

Joined by Jesse Morris on bass, the band defies both gravity and tradition, shifting from powerful old time fiddle dance tunes to crooning early bluegrass harmonies while putting on a darn good show.

Currently they are all the rage up here on the Blue Ridge, because fans are crazy about the drive, the authenticity, the fun and the madness that is “Nobody’s Business”

Searching for that Old Mountain Whum

Malcolm Smith, PhD

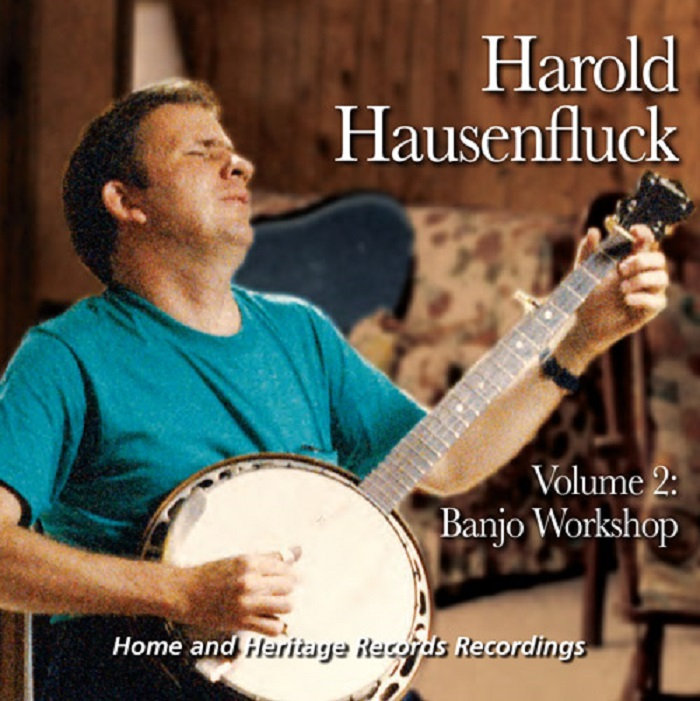

Harold Hausenfluck left us this past year. He took with him one of the greatest set of ears that any old time mountain musician had or probably will ever have. Cantankerous, often rude and definitely politically incorrect, Harold was a fiddler extraordinaire, an accomplished banjo player, a critic of musical approaches and styles, and perhaps, most importantly, an incredible teacher who’s students are some of the greatest Appalachian musicians on the planet. Accomplished current players like Mark Campbell, Mac Traynham, Andy Buckman, Trish Fore, and many others credit their musical proficiency to Harold’s teaching and recordings. Not only was Harold a master musician, he was a lifelong student of mountain music, in search of an authentic mountain sound.

Harold Hausenfluck’s Banjo Recording available from http://www.fieldrecorders.org

Blinded during infancy, Harold grew up with a father who loved old time music and who fostered that same passion in Harold by taking him to experience fiddle contests, concerts, and play parties across SW Virginia. Harold’s first self-taught instrument was the harmonica and that led him to both the fiddle and the banjo in his teen years. Born in 1952, Harold was an eager learner who focused his intense musical capacities on learning from the last of the authentic “old timers” like Wade Ward of Independence, VA.; Glen Smith of Hillsville; Abe Horton of Fancy Gap, Dent Wimmer of Floyd County, Joe Birchfield from Roan Mountain, TN and others. He developed both an extremely solid sense of rhythm and the ability to emulate and dissect the exact fiddle strokes and banjo brushes of the old timers. Thankfully, Harold was fascinated with the medium of radio and recording and left us with hours and hours of his playing and of his self-produced radio shows.

According to Mac Traynham and several others that knew him, Harold was always searching for the illusive “Mountain Whum.” Harold would describe the “whum” as an ideal mix of intonations on the banjo that allowed the instrument to resonate in a certain, beautiful manner, combining perfect tension on the head, a resonant wood on the pot of the banjo, and a forceful, deep method of playing that brought all of the strings into a perfect harmonious sound. Banjoist Glen Smith had it, Harold commented, but Wade Ward did not. Some folks got it on an open backed banjo, some on a resonator banjo. When someone produced the “whum,” it made Harold ecstatic. He could hardly contain his excitement.

For me, the “whum” explains a lot about modern day clawhammer players. It explains why most of us have more banjos under the bed and hiding in closets than we ever admit to our spouses or significant others. It explains why we would pay 40 or 50 bucks to find the perfect stuffing to put in the back of our banjos, from sea sponges to plush toys to specifically manufactured “banjo bolsters” to dampen the overtones and supposedly adjust the “whum” factor. Harold’s keen ears, his life of immersion in old time music, and his intense passion for the mountain sound demanded he search, constantly, for the “Whum.”

Overtones and Ghost Tones

There is another phenomenon that in my mind is closely related to the “mountain whum.” It happened again to me in a recent jam. There were maybe 15 musicians playing together in a great sounding wood encased room – a remodeled grain silo. There were at least three fiddlers locked together in beautiful melody with guitars banjos and bases following their lead and just as I reached the euphoric state that many of us refer to as “the old time trance,” those moments in the tune when you become totally mindful of the tune and the notes rise from your fingers effortlessly, when suddenly I was hearing overtones. Notes were filling the void above the music as if there was a fourth fiddle in the room playing harmonious notes that seemed to embellish the tune in a new and unusual way. I looked around to see who this new fiddle part was being played by. No one. I focused on the lone mandolin player in the jam. It wasn’t him. The fleeting fourth part came and went and soon the tune was over. If I had not heard this phenomenon many times over the years at jams and campouts, parties and practices, I would have been blown away. Where did that fourth part come from?

Turns out that the answer to that question is a worm hole that a person can spend hours crawling through. Basically, there are two schools of thought about ghost fiddles and other sounds hovering above a jam. The first is mechanical the second is purely mental. One camp firmly believes that these notes, tones, voices and sounds are the result of luthiery and of one’s ear sensitivity. Like the “mountain whum,” it is believed that many luthiers seek for their instruments to be carefully calibrated to produce melodic overtones and that this quality increases both the sound quality and the playability of the instruments. Legendary fiddle maker Albert Hash, for example would start each Appalachian Spruce fiddle he built by whumping various trees with a rock to hear the tonal quality of the wood. Others, like guitar builder Jackson Cunningham adjust the thickness and bracing of their guitar tops according to the overtones a certain piece of wood produces.

In other words, ghost tones or “whum” are the mechanical result of certain qualities of tonal wood that cause a note to produce multiple oscillations above the primary note picked, and when those sounds meet the oscillations produced by a variety of strings played together, they produce a new set of sounds that can be heard and interpreted by sensitive ears. This all make sense until you start to ask musicians about the qualities of ghost notes they hear in a jam.

“All of a sudden I heard someone singing words to that fiddle tune. It was clear as a bell, but as soon as I looked around the jam and there was absolutely no one singing that tune!” Over the past two years, while mulling over this writing piece, I have asked over 100 acoustic musicians about the experiences with “whum,” ghost notes, overtones and voices. Some musicians told me it happened frequently in Bluegrass harmony singing, when three voices locked in gospel harmonies produce a fourth part, a harmonious voice. Still others said the “notes” actually sounded like talking, as though there was someone rudely talking over the jam tune. Many explained that they thought it was the old-timers talking from beyond, expressing their likes or dislikes for the way the tune was being played. Although they usually said it with a laugh, this remark often caused me chills.

This leads to the second predominate theory in the academic literature (yes people in academic caves spend hours mulling over this type of thing.) These folks believe that a musical experience is much like watching TV in that the mind is constantly filling in the spaces between, below and above the notes. In other words, when you grab your Cheetos and your remote to tune into the latest Netflix offering, it is a fact that you are only seeing one line of graphic display at a time and that your mind is imagining the rest as the screen illuminates rapidly downward. The belief here is that your mind is rapidly filling in sound between the notes to make a song, and that during this engagement, your mind sometimes fills in things that it thinks should be there, such as tones, notes, singing and yes, even talking. In other words it’s a figment of your imagination, your dream.

So, the question is, for me, are the ghosts of old time music real? Are they the diabolic plot of centuries of fiddle, banjo, mandolin and guitar makers and the councious act of scary bluegrass and church singers or are they the fiction of my imagination? It’s a lot like the ultimate old time question, “Where’d you come from? Where’d you go, Uncle Joe?”

For many years, another related scientific theory was predominate. It goes clear back to 1714 when musical sage and violinist, Giuseppe Tartini noticed that when he played two notes on his fiddle at the same time, they would produce, amazingly, a third sound. He called it a “combination” tone because it consisted of frequencies from both notes. Immediately, and for at least the next 200 hundred years, audiologists believed that this note was created inside a person’s ear by the cochlea rather than being a product of the instrument. Eventually, sometime in the 19th Century a German physicist proved that certain instruments could produce combination or ghost tones on their own. Recently, researchers have gone deeper by comparing paired notes on different violins and separating the sound waves. They found that all five instruments used in the study produced ghost tones, but that the OLDER instruments produced the strongest overtones. They also tested who could hear these phantom notes, by playing the notes for a group of amateur and professional musicians. Over 93% of the time everyone heard the “ghosties.”

Needless to say, this research is only getting started, but current thinking is the ghost is in the instrument, not residing in my ear. It is my conclusion that whatever we’re hearing is real, not an auditory illusion. It is also my opinion that we must all continue, in tribute to Harold Hausenfluck, to keep searching for the Mountain Whum and listening to what the old timers are singing and saying to us.

References:

University of South Wales Physics Department (2023) Tartini Tones and Temperament,Retrieved Nov. 1, 2023 from: https://newt.phys.unsw.edu.au/jw/tartini-temperament.htm

Padavick-Callaghan, K. (2022) Phantom Notes on the Violin Turn out to be a Real Sound. Retrieved Nov. 1, 2023 from https://www.newscientist.com/article/2344992-

A New Legend is Born in SW Virginian

The First “Legends of Grayson County Gathering in Independence

During the first weekend of April, 2022, a new kind of celebration of the rich musical heritage surrounding Grayson County, Virginia was born. The “Legends of Grayson County” was a unique musical gathering, including historic and educational presentations, storytelling, music and dancing, discussions and master led jams. It was part fiddle festival, part class structured learning like Augusta or Swannanoa, and part historical lecture including workshops and master led jams. In what is perceived to be the first of many years of celebrations, the first “Legends” celebrated the life and musical legacy of White Top Mountain Band fiddler Thornton Spencer, as well as the accomplishments of Junior Appalachian Musicians founder, Helen White.

The celebration was held in Independence at the 1908 Courthouse whose museum setting and old time upstairs courtroom converted into an auditorium, set the scene well. The gathering started on Friday night, with a master-led jam led by fiddler Lucas Paisley who helped participants get acquainted with local fiddle tunes. The formal program started with a short lecture on the life of Thornton Spencer, presented by Malcolm Smith who wrote a book about Thornton’s brother-in-law, Albert Hash.

Thornton was born near Rugby Virginia under the watchful eye of both Mt. Rogers and White Top Mountains, the two highest peaks in Virginia. A place where old time music, particularly banjo and fiddle music, has survived in its purest form for two centuries. Thornton became a torch bearer of Grayson’s high country music when his older sister married legendary White Top fiddler and fiddle maker Albert Hash. As a young teenager, Thornton spent most of his time at his sister’s home on Fee’s Ridge, studying his brother in law’s music. Albert showed him how to play the guitar and his love for fiddle tunes began.

One Friday, Albert came to his young brother in law and took a fiddle he had built down off the wall and handed it to him. Albert showed Thornton two tunes and told him if he could play them by the time he got back, he could own the fiddle. After being banished to the corn crib by his sister, Thornton spent three days scratching out those two tunes until he could play them.. He won the fiddle and did not look back for nearly 70 years.

Thornton became known for his ongoing jams at his parent’s country store that stood right near Mt. Rogers school. There many legendary musicians from Grayson would gather including banjoist Jont Blevins, Stuart Carrico, Munsey Galtney, Dean Sturgill, and a cast of hundreds of young people who flocked to learn old time music from the likes of Albert Hash.

In the early 1970’s Thornton met a young college student who was studying ballad singing. He married Emily Paxton who was from Northern Virginia, and a musical collaboration that would last nearly 40 years was born. In the mid 1970’s Thornton and Emily joined Albert and a young banjo player, Flurry Dowe, who had “stopped by” the store and was groomed by Albert and Thornton to become steeped in the mountain style of banjo playing, to form The White Top Mountain Band. Over the next three decades, Thornton would help lead the band to international recognition while becoming one of the favorite old time dance bands in the region. Tom Barr, on bass, and his wife Becky on second guitar and vocals help round out the dynamic sound of the band.

While his brother in law was alive, Thornton became his biggest fan and supporter, playing second fiddle to him in the White Top band, and promoting Albert’s unique fiddle style. During this time, Thornton sought out and learned with Albert, from some of the region’s great masters of old time fiddling. He became well versed on the music of the region and was often sought after for his knowledge of local music as well as for his playing. The band received national recognition, playing at the Smithsonian, The Carter Family Fold, and the 1982 World’s Fair.

In early 1983, Albert Hash died at the age of 62, leaving Thornton to carry on his legacy of preserving and exciting people to help preserve the music of the Virginia Highlands in Grayson.

To that aim, Thornton had helped Emily and Albert establish the first music program at Mt. Rogers school, that was designed to teach traditional music to the young people of the area. They also taught music at the Mt. Rogers fire house, to spread their knowledge of traditional music. The relaxed, but exciting atmosphere that they created at these lessons eventually evolved into the JAM Program when a young counselor in the Ashe County schools in North Carolina named Helen White asked for Emily’s help in getting her program started.

Thornton continued his work as a fiddler, teacher and cheerleader for old time music until his death in 2017. During a magical evening on April 1, 2022 at the Legends event, the White Top Mountain band, now made up of Emily and her and Thornton’s two children, Kilby Spencer replacing his dad on fiddle and Martha who sings, plays a variety of instruments and dances with the band. As the evening progressed, many of Thornton’s former students and friends took the stage in his honor, including fiddler and luthier Chris Testerman, banjoist Larry Sigmon, and Martha Spencer’s own group, The Blue Ridge Girls. At the end of the White Top Mountain Band and Friends performances, Emily Spencer was presented with a handmade plaque honoring Thornton’s contributions to Grayson music.

The evening ended with a Master led jam featuring one of Thornton and Albert’s most celebrated fiddle students, Brian Grim who with his sister Debbie, formed the Konarock Critters one of the most famous powerhouse old time bands from Grayson County. The evening sold out, with the old courthouse rocking with a maximum capacity audience.

The second day began with coffee and donuts with some of the best story-telling and history- recounting names in old time music. The roundtable discussion about Thornton Spencer, Grayson County music and the regions rich heritage was led by an all-star cast of characters. Among those assembled were guitarist and guitar builder Wayne Henderson, musician and author Wayne Erbsen who had lived in Grayson County before moving to Asheville, NC and was influenced by the White Top Mountain Band, Emily Spencer, Rita Scott who learned fiddle from Thornton and Albert, banjoist Trish Fore, Tom Barr who played bass for many years with the White Top Mountain band, and Jim Lloyd who played guitar with the Konnarock Critters. The group provided a monumental morning of stories and anecdotes about the legendary Grayson County old time scene.

Saturday afternoon was dedicated to the memory of Helen White, founder of the Junior Appalachian Musicians program and life partner of guitarist and guitar builder, Wayne Henderson. Helen was a life-long educator and musician who attended both the University of North Carolina and Appalachian State University.

After becoming an elementary school counselor in Sparta, North Carolina, in the early 2000’s Helen noticed that many of her students didn’t have a sense of pride in their Appalachian heritage. As she thought about how much she felt connected to Appalachian music, especially through her partnership traveling and performing with Wayne Henderson, she decided to start involving local students and their families in learning how to play the old time and bluegrass traditions of the area.

Helen recruited local musicians to teach traditional instruments and dance, including banjo, fiddle, mandolin and guitar as well as various forms of old time dancing. The idea spread and Helen was soon directing a regional organization with hundreds of students. It travelled through communities in the region like a virus and before long there were JAMs programs across the mountains of North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee and South Carolina. Although Helen passed at the age of 69 in 2019, her creation has spread to more than 40 cities and flourishes under the direction of Brett Morris, who led the tribute to Helen’s work on Saturday at the Legends events.

Besides sharing Helen story, Brett invited JAM instructors, students (both current and former) and friends of Helen to pay tribute to Helen in music. Of course, Wayne Henderson played some of the tunes he had played onstage with Helen over the years on his guitar. Eddie Bond, a National Heritage Award winning fiddler and JAMs teacher played with former JAMs student and clawhammer banjo master Jared Boyd of the Twin Creeks Stringband.

A fitting and tear filled moment of recognition happened when local musicians Betty Vornbrock and Billy Cornette of the Reed Island Rounders played “Helen’s Waltz,” a fiddle tune that Betty had written to honor her dear friend.

The evening ended with concerts by The Crooked Road Ramblers, featuring Kilby Spencer, Thornton’s son, on fiddle, playing many of his dad’s tunes. Their performance was followed by a reunion of one of Grayson County’s most powerful old time bands, The Konnarock Critters. Brian and Debbie Grim (fiddle and banjo) were joined by Wayne Henderson on guitar as well as Jim Lloyd, playing as a band for the first time in 20 years. Their performance was wildly received with a standing ovation.

Throughout the day on Saturday there were workshops on fiddling, mountain dance, guitar, as well as clawhammer and two finger styles of banjo. Saturday, like Friday was sold out, and the event came to a close late Saturday evening with a master-led jam officiated by Kilby Sp;encer.

“Legends of Grayson County” is the brainchild of two Atlanta based musicians, Steve Soltis and Mark Boyles, who have formed a deep appreciation for the region over the past 25 years and wanted to give something back. Both men escaped their corporate jobs in the city and headed to the Blue Ridge mountains around Independence to fish, hike, and camp along the New River. Those trips inevitably led to their discovery of the area’s rich musical traditions. They became annual campers at the Grayson County Fiddler’s Convention and began to make acquaintance with many of the area’s musicians. In 2021 they founded a not-for-profit called Peach Bottom Partners.

“This is our tribute to the extraordinary musicians who have contributed to the Grayson County sound,” said Steve Soltis, “It’s going to be an annual event.” Soltis and Boyles also enlisted the Grayson County Tourism division, the Town of Independence, local churches and the Historical- Society to help with food, logistics, promotion and volunteers.

According to Boyles, the collaboration was a huge success. “We presented a new kind of immersion into old time music and the people who played and still play it, and our attendees loved it,” he said. Proceeds from this year’s event will benefit both the restoration of Mt. Rogers school into a community arts center and the JAMs program.

Preliminary planning has already begun for the second Legends of Grayson event, scheduled for March 31 and April 1 of 2023. Next year’s celebration will include the life of banjoist Wade Ward and the contributions of musician and organizer Donna Correll, who with her husband, Jerry Correll helped shape the more recent Grayson County sound. For more info visit the “Legends of Grayson Old Time Weekend” on Facebook.

Rhythm and Genes: The Moonshining and Old Time Music of SW Virginia’s Boyd Family

It’s a beautiful early spring afternoon in Southwest Virginia and I’m deep in Franklin County. One of the things that everyone seems to know about Franklin County (named for Benjamin Franklin) is that the writer, Sherwood Anderson, once dubbed it “The wettest county in the world.” I am on Boyd land, just off Dry Hill Road. The Boyd’s have owned, farmed, and worked land in this county since the earliest settlers came to Virginia. They have also contributed substantially to its legendary status since the “Great Moonshine Conspiracy” of the early 1930s and to its renown as one of the natural sources of great old time mountain made music in the world.

Jimmy Boyd believes in genetics. “There’s something about us Boyds,” he told me, “that just put rhythm in us. My daddy played all sorts of things,” he remembered, “but when he danced, his body would just come alive, and people would come to watch. There was an old mountain woman that lived in the hills over there and everybody wanted to watch her dance with my daddy.

As I waited near a beautiful pond on the Boyd property, an old battered red flatbed truck approached hauling its capacity in large round hay bales. Out of the driver’s side popped a larger than life mountain man, wearing a well-worn moonshiner’s hat, a flannel shirt draped loosely over a t-shirt from one or the other old time music festivals. He grabbed my hand, momentarily crushing it in his, and smiled a wry smile. Grandchildren climbed in and out of the truck and then his son, Stacy, jumped in and took over Jimmy’s chores while we grabbed chairs down by the pond. For the next two hours I was in the presence of living folk lore: moonshine historian, storyteller, banjoist, band leader, and proud head of the clan, Jimmy Boyd.

Jimmy’s earliest memories of growing up in Franklin County are of two things that have greatly influenced his life. One is of men making shine along the creek banks and hollers and the second is of hearing old time music at corn shuckin’s and parties and in his own home.

“The two have always just seemed to go together, somehow in my life,” said Jimmy. He remembers vividly being carried on his father’s hip down a long winding path to a still way back in the woods near his earliest home and seeing men standing around a still. “The thing I remember the most is the sweet smell of that corn cooking. Back then, those men made it right, little or no sugar, almost all grain. It smelled so good,” exclaimed Jimmy.

The moonshine really came first. Jimmy’s older brother, Billy, who he looked up to, became involved in working with and for the local shiners in his teens. In the post-Prohibition days in Franklin County, there had been so many families involved in the moonshining business (one estimate in the Roanoke Times was that 90% of Franklin County’s population was somehow involved in its shine production and export business in the ‘20s and ‘30s) and so many of the families relied on moonshine for their income, that the tradition was hard to die. Many of the folks from the Moonshine Conspiracy and moonshine makers warring days with law enforcement didn’t have any other source of income and jobs were scarce for those not fighting in WWII. Some of the best moonshine runners from the area became race car drivers. Others like Jimmy and his brother, joined the tradition and learned the trade of Franklin County whiskey production at young ages.

“I was about 12 years old,” recalled Jimmy, “and my brother, Billy was about 8 years older. When he left home at about 16, he didn’t go to the factory, he went down in the holler to make whiskey,” he said, “He got with some old timers who really knew how to make whiskey. He would make good, clean whiskey.”

“He got me going. I made my first real batch when I was 20, soon as I was big enough to haul a 100 pound bag of sugar. But back in those days we didn’t use any sugar on the first run. It was pure grain, no sugar. We would save back the backwash from that first run, the grain and the yeast, add some barley malt and a little sugar and the yeast would go again, and that’d be our second run, the first sugar,” Jimmy continued, “You could do that four times. Cornmeal and barley malt, and sometimes dry meal.” He continued, “That made the best whiskey. Some folks around here now just make sugar whiskey, that is awful stuff and not good for you,” said Jimmy. “Some people would want that first all-grain run, some preferred the first sugar. It was all good,” he laughed.

He remembered the thrill of heading down to the first barrel of corn mash that he fermented. “It was the springtime, like this,” Jimmy recalled, “You start up that holler to that still and you can smell it fermentin’ and that smell gets mixed with the honeysuckle smells and those flowers, that’s fun,” he smiled. “We enjoyed our work. A lot of that moonshine we made didn’t stay around here. A lot of it was headed up to the city folk up north,” said Jimmy.

There was an organization of labor involved in the process. “At first, I was just the labor at the still site,” he told me. “It was my job to help make the moonshine, ferment the mash and then cook it,” Jimmy said. “Most of the time you had your distillers and then you had someone around who did your furnishings. A fellow that done your furnishings, he would bring you your grain, and when you were done, he would pick up the whiskey and he would distribute it.”

Stacy Boyd, Jimmy’s oldest son, remembers being a small child when his father was making whiskey at a still site on the other side of a ridge near their home. “Our job, when Daddy was shining and we were playing in the yard, was to watch the cars going up the only road near our house,” Stacy said. “We were supposed to count how many people were in the car when it went up the road, and then count how many were in it when it came back down. If there was less people in that car, we had to run over the ridge and tell Daddy, because it was probably a revenue agent being dropped off to find the still.”

Over the years, Jimmy has had his share of run-ins with local law enforcement and has spent an accumulation of nearly a year of jail time for his hobby. “We had to be real careful, back in those days,” Jimmy said, “A lot of times my wife wouldn’t even know where I was working at. Sometimes the people paying us wouldn’t know.”

Watch a short video about Moonshining in Franklin County HERE

The life of a moonshiner in Franklin county had lots of risks. Jimmy recalled getting caught and spending time in city and county jails. “I had been pulling three months and some days in the Rocky Mount jail,” he said, “And the old sheriff, he took a likin’ to us because moonshiners are good people overall. They’ll pay you every cent they owe you and they are just as honest as days are long. Most of ‘em are. Every now and then you’ll get someone who wants to turn the next fella in to get some money, you know.”

Jimmy continued his story, “Well, that old sheriff at Rocky Mount, he took a likin’ to us, you know. We had a year to pull and he made a trustee out of me and then said, ‘Boys, how would you all like to go home?’ Well, that sounded good to me! So, he said, ‘I’ll tell you what, if you paint my jail inside and you get it done, I’ll see that you go home.’”

“We stood around there a day or two, and then he came by one day and looked at it and said, ‘Well, boys I got some good news and I got some bad news. I’ll tell you the good news first,’ he said, ‘You can go home, but the bad news is you got to pay your fine.’”

Jimmy and his partner owed nearly $1200 in fines for getting caught moonshining. “Well, my buddy, he called his wife and he paid his fine,” Jimmy told me, “and he got out and she paid his fine, and then he said ‘I’m gonna come get you out tomorrow.’ So, he did, he went and got the money and paid my fine so I could get out. I had so many kids and I’d been in there three months, I had to get out.”

Jimmy laughed and then recounted the story of how he and his partner got caught. “See we had this still set up, and we were making whiskey to sell. We had what you called the old pots, and they held about 800 gallons a piece and we had four of them set up. They were what you called submarine type pots. We could make 20 cases of whiskey out of each one of them. And we had done run one of them and filled 20 cases of liquor that day,” Jimmy said.

“Well, we was getting ready to cap the second one that day,” he continued, “The old boy that was helping me, he was putting the whiskey out into jugs. Well, I looked down there towards the road and I seen somebody jerk his head back behind a tree. I said ‘We’d better go!’ and so we hit the holler. We went straight into the holler, right straight away from him. Dumbest thing we could ever do. We went about 75 or 50 yards up that holler and there was a fence come down across there. Well, we run right up against that fence, and there was five or six of them on the outside and three or four on the inside and they had us up against that fence,” said Jimmy.

Jimmy got more animated as the story unfolded. “When I went in that morning, I was a little juvenus (sic), anyway, I had on a pair of tennis shoes, so I was ready to run. When they all gathered around us right there, I was gonna break and run across the branch. Well, when I jumped across the branch, I sunk into the mud about that deep!” Jimmy motioned towards his elbow. “And one of them jumped on my back. Yea, one of them ABC bosses jumped on my back! And, well I knew I wasn’t getting out of this, so I just gave up.”

“So, he said to me, ‘What’s your name,’” Jimmy went on. “Well, I knew I didn’t have no ID on me, you know. I didn’t carry no identification, no driver’s license or nothing, so I told him, ‘John Holly.’ It come to me just like that. And then he said, ‘Where you live at?’ and I said ‘Bassett, Virginia.’ See I was down towards Basset working you know,” Jimmy smiled a wry smile.

“So, they put handcuffs on us,” he recalled, “And took us back to the still site. They read us our rights. Then they asked us, ‘If we take those handcuffs off are you all going to run anymore if we take those handcuffs off?’ And I said, ‘I don’t reckon. It’s no use. You know my life’s history, don’t you?’ Of course, I hadn’t told them nothing and had no driver’s license, you know. They didn’t know nothing about me. So, they took the handcuffs off of us, and, we had put some soda pops down in the branch to cool and some of them got soft drinks.”

“Well,” Jimmy continued, “They got to laughin’ and chopping the still up, and laughin and a choppin’ and a bustin’ the jugs up. Well, I caught them all five or six yards away from me, and I hit that hill a runnin’. I had to go straight up a hill, just like that over yonder,” Jimmy paused dramatically. “Shooting! You’ve never heard such shooting! They probably shot 25 times. And there didn’t but one take off after me. I don’t know if he were the fastest one or what. But he was just right on my heels going up that hill.”

“When I got on top,” Jimmy remembered, “I was a little bit ahead of him and I got out front of him about eight or ten yards. Can you imagine run all the way to the top of that hill over yonder? You’re gonna’ be out of breath! I wasn’t but about 25 years old at the time. I was in good shape. “Well,” Jimmy said, “We both got down to a rock wall going out through the woods and jumped it. Finally, we came to this little dirt road going off down the woods that hardly anybody travelled, and I hit that little ol’ dirt road and had got about from here to that dirt pile yonder ahead of him,” Jimmy pointed at a small dirt pile about four yards away, “And I looked back to see if he had gained any on me.”

Jimmy then imitated his pursuer. “He hollered, ‘Look back you SOB, I’ve got a good notion to blow your head off.’ I didn’t say nothin,’ Jimmy laughed, “I just kept a haulin’ it. Well, I went up there and went through an old farm house yard and got over there and hit that hill, and I lost him. But we went about five miles and we come out in Henry. Right in the little town of Henry. I come out on the right hand side of the road about a hundred yards, and he come out right in the middle of town. I don’t know if he was following me or what, but he didn’t catch me that day.”

“I stopped at a man’s house,” said Jimmy, “And asked him if he’d take me to a certain place and he said, ‘Well I’m in my bed trying to get some rest,’ and then he looks at his wife and says ‘Take this man where he needs to go.’ So, I got clean away from them. Now that boy, the one who got caught with me, he was just 18 years old. He was just a young’un. They tried him. And I’m pretty sure when they tried him, he told them who I was, but they weren’t in no hurry to come and get me. It was three months before they came and got me. They sent a United States Marshall after me.”

“By that time, me and a buddy were making liquor somewhere else,” Jimmy continued, “And I lived in a house just down the road here. The house set on one side of a little creek and it had a walkway going off of the porch to a spring house over on the other side of the creek. And we had 60, no I can’t remember, maybe 160 cases of liquor packed into that little spring house. See, sometimes when you’re making whiskey, it’ll sell good for maybe three or four weeks and you’ll get rid of every drop you made and more, and then again, you may have to hold it for several weeks.”

“At that time,” said Jimmy, “it was cold, dead winter. We had it packed up in there. One evening I had been down to Ferrum with my whole family, and I was coming home and looked over in my yard, and there was a bunch of State Troopers and deputy cars about a dozen or so sitting in my yard. So, I just went on by, I drove right past them. And someone recognized my car and they tore out after me. Well, here they come, chasin’ after me down the road for about two miles. Now I didn’t try to outrun them or nothing, cause I had the whole family with me. Oh, I wanted to jump out of that car and run so bad, I could hardly stand it. But I decided I’d just stay with it.”

Jimmy then told me, “When they stopped me, I just sat there and they come up there to me. There was the nicest young fella, his name was Bob Johnson and he was a United States Marshall. They sent a Marshall after me. He arrested me and read me my rights and got me in the car with him and told me all about the reasons he was after me. And you know, that man stuck with me like glue. I don’t know why he took a liken’ to me. When I went down there, he was just the nicest feller you have ever seen. Later on, he become a preacher. And now he plays old time music! He sure does, I’ve played some with him!”

“Anyway,” Jimmy went on, “we had about a half inch of snow on the ground. And it was all over that walkway going to that spring house. They put me in jail that night and the next morning this old fella come over and bailed me out. I went home. All night long I’d been worrying, afraid they were going to find all those cases of liquor. All our profit was packed up in that spring house. So, when I come home next morning, I went and looked at their tracks. Well, they had been all around the house, looked in every window, looked in every door. You could see their tracks. But there wasn’t a single track going down that slippery walkway to the spring house. That was in 1972.”

One of the things that I was most curious to find out from Jimmy was what he saw as the relationship that has always seemed to exist between making and drinking moonshine and old time music. He believes they go hand in hand because “They’re both about having fun, dancing, and having a party. But they’re also both something you can make yourself. Self-made fun!” he said, “But moonshine, it settles your nerves and you’re more carefree when you take a drink.”

“I’d known a woman that used to come around,” Jimmy told me, “Her name was Brona Bennett. She told me one day after the Dry Hill Draggers was playing, ‘You all always get to playing a lot better after you take a little drink. Your music flows better, blends better.’ So, I always figured that when your music and your moonshine get together, they flow,” said Jimmy.

It was Jimmy’s brother, Billy, and a great uncle, Ted Boyd (of Orchard Grass fame,) who first got him into playing old time music. Surprisingly, Jimmy didn’t start seriously learning the banjo until he was 30 years old, although he had listened to and enjoyed old time music since he was two years old. Jimmy was just starting out, borrowing one of his brother’s banjos to learn with when he went to his great uncle and said, “I don’t know if I’ll ever figure out how to play this thing.”

Ted Boyd looked at Jimmy and replied, “Well I don’t know either, Jimmy, but you have good timing.” That was it. Timing. Jimmy began to look on the banjo as a drum. Learning a lick or two from his older brother, he began to develop what would become one of the most recognizable clawhammer banjo sounds in old time music. Not just Galax style rollicking banjo, certainly not the melodic Round Peak style of Tommy Jarrell and Kyle Creed, but Jimmy Boyd style, a rhythmic romp that would take him to play in some of the most prestigious old time music venues on the planet and with some of the greatest players of his times.

“My brother was the backbone of what I learned. He passed away, though, of lung cancer when he was just 50,” Jimmy said, “But he got me going and encouraged me to put together a band. He helped me learn a few tunes and to play them fast and hard with a lot of rhythm.”

“Well once I had a few tunes down and noticed they brought the dancers around and they loved ‘em, and danced. It started looking like everyone wanted to come around and dance when we was playing, you know. At somebody’s house party or front yard,” said Jimmy.

Then Jimmy revealed the method behind his style of banjo playing. “You see, then, I stopped trying to learn individual tunes. I concentrated on the dance lick on the banjo. It was a lot of pleasure, playing. I found that if I strummed down a little harder on that banjo, I could make them people dance harder,” he proclaimed.

“Some old fellow told me one time,” said Jimmy, “he had been coming around where we’d been playing a lot and he said, ‘I finally figured out what you’re doing,’ he was talking about that lick that I’ve got, ‘You’re playing something like the tempo, the rhythm and the tune all at the same time.’ I laughed and I said, ‘Well that might be what I’m doing, but all I can do is what I know, you know.”

After Jimmy got his lick down, he first started playing with a neighbor who played the fiddle. “There was an old man that lived up the road here, he played with us on the first record that we made, named Murphy Shively. He was the type of fellow that if he could get out of doing something the hard way, that’s what he’d do. His ancestors are buried all around here and his daddy was a fiddler, too.”

“He said his daddy would tune up his fiddle and banjo and go out of the room and tell Murphy, ‘Now don’t you be touching those instruments. They’re all in tune.’ Well as soon as his daddy would leave the room, he’d make a dive for them. And he learned to play that fiddle like Posey Rorrer did, that played for Charlie Poole, with the least amount of effort that he could put out. And Murph had some of the best rhythm of anybody that I’ve ever sat down and played with. When you would sit down to play with that man and he’d start a tune, it would just lift you up, and take you along with it. His music would do that to you! He put everything in such an easy gait that it was a lot easier to play.”