THE APPALACHIAN STRING BAND FESTIVAL “GLUE”

Some say “home” is where your story begins. Down an abandoned road off Route 60 near the ghost town of Winona, WV, sits a humble home near a now defunct coal mine. If you were to step on the porch of this house and politely knock, you surely would be welcomed in.

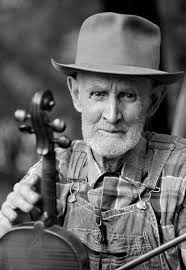

Once inside the main room of the small frame house, built during the glory days of West Virginia mining, you would find a smiling older man standing under the mounted head of an enormous buck deer with antlers taking up much of the rooms ceiling space. The amazing thing about this mounted buck is that each and every spike of those antlers is draped with a hat or t-shirt. Each of these adornments displays a different year’s logo and commemorations of the Appalachian String Band Festival held annually since 1989 at nearby Camp Washington Carver, in Babcock State Park.

Should you engage the owner of this display, you would quickly learn that you are not dealing with an ordinary mountain dweller, but the unofficial “Mayor” of the annual gathering of musicians from around the world known affectionately as “Clifftop,” and that this man takes that moniker very seriously.

You would also learn that each of those garments has a revealing story behind it, which will be related to you by a master Appalachian storyteller who, since 1992, has dedicated his many skills and his deep love of people to the musical community of two to four thousand who gather for nearly two weeks each summer to play the music of the mountains.

Although Floyd Ramsey retired several years ago from his official job, the real exact title of which is always in dispute, he can’t stop spending his year preparing for and greeting the thousands of travelers who come from around the region and across the world to participate in the West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture, and History’s Appalachian String Band Music Festival each year.

Over the years Floyd’s job has been referred to by others and West Virginia’s State website as Camp Washington Carver’s “Assistant to the Director,” “Head of Maintenance,” “Building Laborer.” If you ask Floyd himself, the answer is succinct, “maintenance,” he drawls. Most String Band campers would disagree. They respond with descriptions like “rattlesnake wrangler,” “that guy who blows the whistle,” “fix it guy,” “dispute settler,” “that guy who pulls campers out of the mud,” and many more practical titles. In the end, perhaps longtime Clifftop camper and musician Rob Coulter, from rural Craig County Virginia, puts it best, “Floyd is the glue that holds Clifftop together.”

Floyd has done all these things and much more. Born in Winona, “Up on top of Flannigan mountain,” as he puts it, he has lived in Fayette County about six or seven miles from Camp, his entire 70 years. His partner and girlfriend, Jessie, have been together more than 40 years. Together they have raised three boys and been active in the area’s community life. “She told me she didn’t want to ever get married,” said Floyd, “because she was afraid the good thing we have might change.”

Before joining the staff at Camp Washington Carver, Floyd held a variety of jobs locally and for the state. In the 1970’s when the area coal mines were in full operation, he even worked for a year as a coal miner. One of his jobs for the state that he is most proud of is helping to build the Glade Creek Grist Mill in Babcock State Park that Washington-Carver is a part of. Set on top of a boulder strewn stream, the mill is a working replica of Cooper’s Mill that was once located nearby, according to West Virginia Park Service. The mill was pieced together with original parts that were collected from much older mill ruins in the area. Floyd and his coworkers constructed the mill in 1976, and since then it has become the most photographed mill in the U.S and is famous around the world.

“I didn’t know nothing about the festival when I got hired here,” said Floyd, “They just told me it was a music festival. Floyd told his superiors before coming to work at Camp Washington Carver that if he didn’t like what was going on, he wanted to work somewhere else. That never happened.

“From the minute I came here, I loved this old Camp,” Floyd explains, “And then I met the people. I’ve never met better people than the folks who come to camp and play music here,” said Floyd.

Taking care of Camp Washington Carver and getting it ready for the influx of campers each summer has to be a daunting task. Built in the late 1930’s and early ‘40’s, the camp initially served as the state’s first state-wide camp for African American 4H members. It’s cabin-like structures and 90 year old infrastructure requires constant attention. Floyd and his coworkers spend weeks each summer preparing the buildings and grounds for the strain of thousands of musicians using the facility for more than two weeks in late July and August.

Named for West Virginians Booker T. Washington (who worked in the local coal mines) and George Washington Carver, the camp boasts the largest log structure of its kind in the world, Great Chestnut Lodge. It is used for several events throughout each summer including camps, reunions and weddings and is featured on the National Park Service’s African American Heritage Trail, but the String Band Festival is by far its heaviest use.

Each summer Floyd and others mow, groom, and meticulously prepare the large camping grounds by clearing downed trees and limbs, filling in potholes, dealing with rain damage and flooding in the legendary “bottoms” and attempt to relocate snakes, bears, bees, wasps and other wildlife that might not be good camping companions. Then the campers arrive.

One of the discerning features of the camp that has become an icon to participants is the camp’s water tower, located on the highest point on the camp grounds known affectionately to attendees as “Geezer Hill,” named for the propensity of older campers to congregate their campsites there.

Most people assume that the limited water supply comes from that tower, but in reality providing flush toilets, sinks and showers for attendees is much more complex.

“The water is pumped up the mountain from a well that is a mile and a half away, treated, and then held in large underground storage tanks,” said Floyd. “It’s always a battle,” keeping enough water flowing for the number of people we have.” Accordingly, Floyd and the staff have to regulate shower hours and restrict the use of water at times.

Beyond water management and groundskeeping duties, maybe Floyd’s greatest skill is in helping to manage camper behavior. Putting thousands of musicians, their friends and families together for two weeks can create some chaos and require some minimal rule enforcement and that duty has also been part Floyd’s duties.

“When we first met Floyd, back in the first years, we realized he had the ability to help people follow rules without causing too much commotion,” said the festival’s co-founder, musician and original camp host, Will Carter. One of the early Directors decided that each camping area should be clearly laid out, with strict boundaries. He set Floyd to chalking off camping areas and numbering each one. Will didn’t like the idea and argued that “if we treat these folks as adults, they’ll work it out and respect one another.” Floyd whole heartedly agreed and set about erasing all of the boundaries.

Consequently, a broad patchwork of musical communities have evolved. From the top of “Geezer Hill,” to the youthful “bottoms” you’ll find camping clusters of like-minded musicians, gathered by genre, i.e., “Cajun Land,” geography, “Charlottesville” or just silliness, “Moose Camp.” Over the years, Floyd has managed to study, understand, and have friends in each of the more than 50 separate camping communities that have formed, evolved and grown.

That community knowledge has proved invaluable to some campers. One year a young man that everyone knew as just “Fiddler” came to Floyd looking for water and Floyd helped him fill some large jugs and hauled him and the jugs backed to his camp. Later in the week, Floyd was contacted by staff who had received a phone call for someone among the three thousand campers known as “Fiddler.” The caller said that his mother had passed away and they needed him to come home. Astonishingly, Floyd knew exactly where to find him and delivered the important message and was able to pass it along in time for “Fiddler” to make the funeral..

Something that makes Floyd’s referee duties easier, is that for the most part, each group tends to solve its own problems without involving staff. “I remember one year a group had a rough character who was causing problems, and before that day was over I saw them drive that man to the entrance and tell him not to come back,” recalled Floyd, “That’s the way it usually works, they just take care of it.”

.If you asked Floyd about the hardest part of his job over the years he is quite clear. “We’ve had two deaths here,” he’ll tell you, “That’s hard on all of us.” The camp has medical staff, but maneuvering ambulances and responders into the intricate web of campers and dealing with protocols can take hours and weighs heavily on Floyd and the rest of the staff.

Legend has it that Floyd has used whistles, loud airhorns, shutting off lights and lanterns and a variety of other methods to shut down late night jams and dances that have gone on just too long.

In addition, Floyd’s skills as a rattlesnake and bear wrangler have also become part of Clifftop’s lore. The biggest snake that Floyd recalls he had to remove from a camper’s area was a six foot Timber Rattler. Using a snake handling tool, he wrestles the snakes he relocates into gallon buckets with plexiglass tops because so many of the campers from far away are curious. One can find many photos and videos of Floyd’s snake removal on YouTube.

“The music vibrates the ground,” said Floyd, “And the rattlers are attracted to the vibrations.” Thus, even the camp’s wildlife are drawn to Appalachian string band music.

One camper recalled asking Floyd what happens to the snakes he caught. “Well, I can’t kill them, because they are protected,” answered Floyd. Then a familiar twinkle, known to hundreds of campers overtook Floyd’s face as he lied, “I just cut off the rattles and then they can’t bite anybody!” More than a few gullible campers have succumbed to the mountain man’s sense of humor.

Floyd’s role as rule enforcer is clearly balanced against his deep caring for people. He has hauled hundreds of stuck campers out of mud, helped parents find lost children, comforted folks not used to the mountains’ furious storms, removed bears from under campers and settled disputes between camp sites, all with very little expectation except the friendship of the folks he’s helped. Roy Clark, Jr., son of the famous Hee Haw start, for example, was totally stuck one year and told Floyd, “If you can’t get it out with the tractor, just open the windows and let the squirrels move in.” When Floyd got him unstuck Mr. Clark tried to give him money. When Floyd refused, he offered a CD he had recorded instead. “I’ll take that,” said Floyd. In Floyd’s home you’ll find a large stack of old time CDs, right next to the T-Shirts and ballcaps hanging off the buck representing a lot of hard work and a lot of friendships.

With more than 20 years of service to Camp Washington Carver, Floyd retired from the State of West Virginia in 2019 with one condition, that the State would let him come back and work at the String Band Festival every year. 2025 is his sixth post-retirement year greeting Clifftopers, telling stories and helping thousands of musicians have the experience of their lives..

“He has become legendary,” said Will Carter, “Just one name, like Bono, or Madonna, or Elvis.”

Bands have been named after him in Rhode Island and songs have been written about him in Baltimore. One camper from New Hampshire recounted that among younger campers in the “bottoms” stories and cautionary tales are told late at night about Floyd’s antics, passing on tales about rattlesnakes, bears, and rule enforcement..

One thing is for certain. Floyd and The Appalachian String Band Festival at Camp Washington Carver are synonymous. He has become not only the glue that holds the festival together, but part of the folklore that makes the festival beloved by so many. And now, Floyd is joined on the crew, full time, by his oldest son, Kenny, who is learning the ways of Clifftop and Camp Washington Carver. When Kenny was invited to join Floyd and the crew, he hesitantly asked his dad, “What kind of people are these folks, dad.”

“The best people in the world,” replied Floyd. The tradition and the stories will continue…