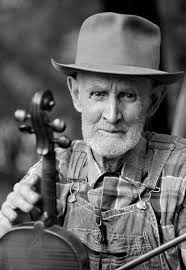

(Photo by Mark V. Sanderford)

A wise family therapist once observed that families who can tell family stories and laugh together are healthy families. Well, if that’s the case, the descendants of Norman (“Uncle Norm”) Edmonds are beyond healthy, they’re well. On a misty early fall evening shortly before Hurricane Helene would wreak havoc on SW Virginia, laughter and stories rocked the rafters of the Laurel Fork Community Center. Gathered together at my invitation were Norm Edmond’s granddaughters Crystal Goad, Brenda Meares, Rita Goad Biggs, and Rhonda Anderson; grandson Ronald Sawyers; and Jennifer Bunn, Norman’s great granddaughter. They were there to share their collective memories of the legendary SW Virginia fiddler affectionately known to everyone as “Uncle Norm.”

It was late September of 2024 and in just a week I was going to host a gathering of musicians on my farm near Laurel Fork and close to where Uncle Norm had lived to celebrate his life and music. The weekend gathering was to include lots of music and community as well as presentations from musicians and family members. Then, just a day before the gathering all Hell broke loose as we endured the very tip of Helene’s wrath. The celebration was cancelled for now, but the stories and laughter of the Edmonds family linger.

Learning to Play

Uncle Norm, whose mischievousness was well known, probably would have relished the thought of a hurricane disrupting our celebration. Born in 1889, to Scots Irish parents who had immigrated to Virginia, Norm was one of four brothers, all of whom took after their father who was a lover of music and a fiddle player. Norman was born in Wythe County, just past the Carroll County line, nine miles from Hillsville in the small community of Patterson. All that remains today of Patterson is a small community center and the 200 year old building that currently houses Carpenter’s Grocery. At the time of Norman’s birth, it had been settled by many immigrants, mostly from Germany, which may explain why Norman’s father spoke German well and Norman knew enough German to later tease his grandchildren with.

His father, John Edmonds, played a homemade gourd fiddle, and from an early age, Norm, the youngest brother, wanted more than anything to learn to play that fiddle. He was so taken with hearing his father and brothers play music that he would do nearly anything to learn. He had the craving and it wasn’t going away. At about the age of five, Norm would wait until his father and older brothers had gone out to work in the fields and then sneak into the closet where the precious fiddle was kept and, carefully imitating everything his father had done, try to scratch out a tune. It didn’t take long for Norm, who like his brothers seemed genetically disposed to musical ability, was playing many of his father’s civil war era fiddle tunes, having kept them in his head. His fingers seemed to fly up and down the neck and he soon mastered the complexities of bowing just by experimentation.

One evening, as the family was gathered in the small parlor of the house, John Edmonds asked his youngest son if he wanted to learn to play and handed him the old gourd fiddle. According to the family, every jaw in the room dropped as young Norman begin to play his father’s repertoire, note for note. It seems that this sneaking about to learn to play is some sort of family tradition among the Edmonds, as two of Norm’s grand-daughters and a great granddaughter related how they had snuck to family instruments and picked them up while their parents weren’t looking. In great granddaughter Jennifer Bunn’s case, it was Uncle Norm’s very fiddle that she snuck out to play and now, years later she plays it regularly. The room at the Laurel Fork shook with laughter and acknowledgement as each of the women disclosed their mischief.

The tunes that the older Edmonds played and taught represented the tunes he had learned from his father, Uncle Norm’s great grandfather, but were now “appalachianized” by the influence of local styles and tunes that his neighbors played and the melodies that made the rounds during the Civil War. As young Norman’s fiddling developed, his tune list reflected nearly 200 years of Appalachian music and like other fiddlers of the region at the time (Tommy Jarrell of Mt. Airy, NC; Henry Reed over in The Narrows, VA; Fulton Myers of Five Forks, VA: and a host of fiddlers in Galax) brought pre-civil war tunes back into the local fiddle repertoire. Norman’s capacity for learning and keeping tunes solely by ear seemed remarkable. Among the tunes young Norman learned from his father were “Walking in the Parlor” (He reportedly loved to play it while Norm’s mother, would be making breakfast for the family and he’d sing it to her “Walking in the parlor/walking in the shade, Walking in the Parlor with a pretty little maid.”

Other tunes that came from Norm’s father John included “Old Aunt Nancy,” “Lucy Neil,” “Ship in the Clouds,” and one of John’s favorites “Hawks and Eagles.” It is speculated that “Hawks and Eagles” was actually a Wythe County tune, passed along in the mid 1800’s. John and later Norman would sing words to it, too:

“Hawks and Eagles, going to the mountain,

Hawks and Eagles going to the mountain.

Hawks and Eagles going to the mountain-

Boys and girls, you better get away.”

John had learned tunes from his father as well as other musicians in Virginia. His earliest fiddle was a cornstalk fiddle, a tradition he taught his children how to make. “You could get a lot noise out of those things,” remarked one of Norman’s sons. As John and his four sons held regular sessions and at least one of Norm’s brothers also played the fiddle, Norman began to clawhammer the banjo and soon became adept at playing it both with his family and other local fiddlers. Norm also taught himself the guitar and the pump organ, so he could play in a variety of situations.

In 1917, at the age of 28, Norman fell in love with Fedella, a beautiful ballad singer who was 16, and they were married and moved to the Willis, VA., area. Norman was sort of a “jack of all trades” and subsistence farmed; growing a garden and keeping livestock, but continuing to get out and play music with friends and neighbors. He and Fedella (often known as “Dean”)were also raising a family of nine children, including six boys and three girls. They made sure that each of their children appreciated music. Playing with their father or singing with their mother and learning to dance was part of the family’s heritage to be preserved and passed on.

Norman and Fedella (or “Dean”)in their later years. (Photo by Mark Sanderford)

The Big Bang

Besides playing music with his family, Uncle Norm continued to seek out local musicians to play with. One of his favorite banjo players was a man from the Laurel Fork area of Carroll County by the name of J.P. Nester (1876-1967) who most folks referred to as “Pres” after his middle name, Preston. Pres played the mountain clawhammer style of the region and was crisp, clear and powerful in his delivery. He also sang well and learned many of the old tunes of the Galax region. By day, he would operate the Hillsville telephone switchboard, and then hike out into the Blue Ridge at least seven miles, to where Uncle Norm was living, and play until midnight. The two became good friends and were in demand. Their style, according to many folklorists such as Charles Wolfe, represented the original fiddle/banjo duet style of the Blue Ridge well. They were asked to play for house parties, school dances and pie suppers around the area.

Reportedly, it was very hard to get Pres to travel out of the area. He didn’t much care for automobiles or trains and preferred the confines of Carroll County, where he could walk without much bother. After playing regularly for a furniture store owner in Hillsville, a once in a lifetime opportunity came along. The furniture man had been approached by an RCA executive from New York, who was setting up a field recording studio in Bristol, TN., 100 miles from Hillsville.With much coaxing, Norm convinced Pres it was worth the money and travel to go down and be recorded by the RCA representative, whose name was Ralph Peer.

In August of 1927, A.P Nester (Nestor) and Norman Edmonds recorded four sides at what is now know as “the Big Bang of Country Music” or simply the “Big Bang.” Among the other musical “discoveries” Peer made during those sessions were soon to become legendary figures in early country music, including The Carter Family, Jimmy Rodgers, The Shelor Family, Blind Alfred Reed, Henry Whitter and a host of others. Uncle Norm’s name was not highlighted on the recordings. They were simply listed as “A.P. Nestor (sic.)” The two musicians recorded four sides for Peer. Two of the recordings were released by RCA later that year: “Train on the Island” and “Black-Eyed Susie.” Norman’s fiddle soars above Pres’s powerful banjo on both cuts forming a nearly perfect example of early string band music from the Blue Ridge.

Two other sides the duo recorded mysteriously disappeared in transit to Peer’s New York office. “John My Lover” and “Georgia,” would never be heard, and purportedly the two remaining tracks would be the only recordings we have of Pres Nester’s playing. To add some insult to the event, Peer misspelled Pres’s last name (“Nestor”) and subsequently every re-release and nearly every historical account of the collaboration between Norman and Pres Nester has wrongfully attributed his playing and singing to “J.P. Nestor.” His and Norman’s rendition of “Train on the Island” remains one of the best examples of old time string band music and has been included in countless anthologies of music and dissertations about the music. When self-proclaimed folklorist Harry Smith released his “Anthology of American Folk Music” years later, he included the tune and the misspelling of Pres’s name. To this day, nearly 100 years later, there are hard feelings in the local area about the misspelling.

J. Preston (Pres) Nester’s grave marker in Cruise Cemetery near Laurel Fork. Correctly spelled.

Currently there are no other “Nestors” in this geographic area, but there is a large population of Nesters. One often told local story recalls that in the early part of the last century an itinerant preacher told the Nester family members that “Nester” had uncouth connotations and they should change their names to the more stately “Nestor.” According to the tale, all of the families that changed their names to Nestor were shunned locally and eventually they relocated to the mountains of West Virginia where the name has flourished. In any account, the lone grave of John Preston Nester, banjo player extraordinaire, rests beautifully on a mountain near Laurel Fork, VA., in a small cematry overlooking the valley of the Big Reed Island Creek, with the correct spelling of his name. Recently, the Museum of the Birthplace of Country Music in Bristol, that is dedicated to preserving the importance of Peer’s recording sessions, has made an attempt to right the wrong done to Pres’s legacy by correcting the spelling in their exhibits and displays.

The Music House

When Uncle Norm moved his family to a home closer to Hillsville, just off Rt. 58, the importance of passing on his musical heritage became a priority for him. With his family’s help he built a one room outbuilding, specifically for family gatherings to play music. They constructed the music house out of cinder blocks, carefully filling each block with straw to add “soundproofing” for both the walls and wooden floor. Uncle Norm wanted to be able to practice and record his music here. Uncle Norm supported his family by doing a variety of jobs including working on the railroad, working at sawmills, building furniture, gardening, playing music and piecemeal work where ever he could find it. On one trip to Indiana, he bought a pump organ and brought it back to the Blue Ridge only to find it was too big for most of the house, except in the bedroom, where it landed and stayed. He would play hymns on it while the family sang from the bed and the hallway outside.

As his children aged and started their own families, it became a tradition for the local family to gather for music on Sundays before church. They would gather in a circle of chairs at 7:30 and play for two hours solid, before joining in a huge breakfast, finished just in time to make it to the 10:00 Presbyterian Church service down the road. His grandchildren all remember these Sunday rehersals as jubilant gatherings with Uncle Norm leading the family in tunes and songs, usually with his small dog, Penney, seated on his lap and looking longingly into Uncle Norm’s beard. Here he and his boys and sometimes grandchildren, played while some of the daughters danced and his wife set the large table in the music house with a Sunday feast.

Rufus “Berry” Quesinberry, Uncle Norm, and Paul Edmonds (photo by Alan Lomax)

In the 1950s, a local banjo player named Rufus Quesinberry began to join the family for Sunday practice and became Uncle Norm’s go-to accompanist, along with various configurations of his sons, often including Paul, John, and Cecil on guitars and Nelson on bass. He aptly named this mostly family band, with rotating banjo players, “The Old Timers.” About 1955, Uncle Norm was requested to play for 15 minutes every Saturday morning on a local radio station while the studio announcer shared local grain and hog markets. Norman’s son, Rush, dutifully collected these shows on tape, and they later became the basis for two volumes of recordings released in 2015 by the Field Recorder’s Collective (FRC 301 and 302, 2015). The pleasant banter between the announcer and Uncle Norm makes for great listening, as does Uncle Norm’s playing. The show continued until 1970, when Norm, at the age of 81, hung up his fiddle.

During his 60s and 70s, Uncle Norm’s music career thrived with performances at various fiddler’s gatherings, contests, local dances, and social parties. The onset of the “great folk scare,” brought on by the release of the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, kept interest in Uncle Norm alive among students of Old Time music, and many traveled to hear him play and learn from his vast repertoire of fiddle tunes. One such “folkie” was the great folklorist and field recorder from the Smithsonian, Alan Lomax, who came to Hillsville and recorded Uncle Norm and the Old Timers in August of 1959. He recorded a variety of tunes including “Sally Anne,” “Lonesome Dove,” “Walking in the Parlor,” “Salt River,” “Greasy String,” “Breaking Up Christmas,” and “Bonaparte’s Retreat.” The Old Timers that day consisted of Norman, son Paul on guitar, and Rufus Quesinberry on banjo. (These recordings are accessible at https://archive.culturalequity.org/solr-search/content/list?search_api_fulltext=Norman%20Edmonds)

Lomax’s interest in Norman and the subsequent release of some of the recordings he made brought young people flocking to his door and found his Sunday sessions and breakfast often joined by strangers from as far away as Ireland and England as well as tune seekers from up and down the East Coast. Norm and his family welcomed all comers and he was excited to pass his musical heritage on to a new generation of players.

Although Norm and The Old Timers often played at the famous Galax Old Fiddler’s Gathering, Norm never placed in the individual fiddle contest, but he and The Old Timers placed fourth in the 1964 old-time band contest.In 1970, Uncle Norm was an honored guest at the Galax festival and was asked to play on stage. With a great sense of tongue-in-cheek, he boomed out a version of “Monkey on a String,” and the 81-year-old fiddler brought the crowd to its feet. It was his last public performance.

Legacy

(Photo by Mark V. Sanderford)

As Norman and Fedella moved into their later years, their kids worried about them being so far from town with so much to manage and they built a small comfortable cabin for the folks to live out their remaining days, closer to Hillsville. Uncle Norm passed away in November of 1976. He was 86 years old. Fedella Edmonds lived on until 1992. She died at the age of 92. When I asked the gathered grandchildren and great granddaughter of Uncle Norm what they thought music meant to him, they were unanimous in their response. “Family legacy,” they all agreed.

Much of Norm and Fedella’s later lives involved being active in the lives of their children and especially their grandchildren. All of them remember the music and the gentle teasing their grandpa would give them. Often he would blurt something out in German to startle them or tell a joke and make them laugh. They sometimes would get him back. For example, Norm would hide his “hooch” on top of the refrigerator and sneak it out to the music house to take a snort now and then, being careful not to let the grandkids see it. When the bottle got lower and lower, Uncle Norm, who wasn’t a steady drinker, could not figure out what had happened. He never suspected that his granddaughters were climbing up on chairs to get the bottle and pour some out whenever he wasn’t looking. It was evident that the Edmonds house was filled with love, music, and a deep respect for family and legacy.

Besides the tapes from The Oldtimer’s radio show, preserved by the Field Recorders Collective, only one other album of Norm’s music survives. In 1973, Davis Unlimited Records released “Train on the Island: Traditional Blue Ridge Mountain Fiddle Music.” On the album, Norm and banjoist Rufus Burnett recorded in the classic fiddle/banjo style of the region. Included are newer versions of the two songs that launched Norm’s career; “Train on the Island,” and “Black Eyed Susie,” as well as tunes that Norm has become well known for such as “Ship in the Clouds,” “Lucy Neil,” and his unique version of “Hawks and Eagles.” In the 1990’s due to demand the album was rereleased on CD.

Tragically, in 1998, Uncle Norm’s son, Lewis “Rush” Edmonds died in a house fire. Rush, who had a keen interest in recording technology had recorded years of radio shows and years of family gatherings in the music house that Norm had built and those years of tapes went with him. No other recordings of Norman Edmonds and his beloved Old Timers exist.

Norm’s family legacy carries on among his grandchildren and great grandchildren. Nearly every one of them plays some type of instrument or has a deep appreciation for the music of the mountains. Nelson Edmonds, for example, was one of Norm’s sons that everyone called, “Harry.” Harry not only played a variety of instruments but built guitars and fiddles also. He encouraged his son, aged 5, to sit down next to his Grandpa and learn how to move the sticks like grandpa played the fiddle. After that, he rarely got to play with his cousins at family gatherings because his dad wanted him to fiddle.

Soon, Jimmy was playing so well that he became a fixture at the family gatherings in the music house. By the age of 10, Jimmy was not only playing with his grandpa, but would accompany legendary banjoist Wade Ward on stage as part of the legendary Buck Mountain band from Independence. Jimmy carried the family legacy of music on to win the fiddle category at Galax and many other contests, become a sought after multi-instrumentalist, a producer of the Carolina Opry, and the builder of over 300 high end acoustic guitars. Jimmy also played a fine clawhammer banjo style that he learned from Wade Ward, and one year at Galax took first place in front of Wade who placed second.

Another granddaughter of Uncle Norm’s, Barbara Poole (1950-2008), Jimmy’s sister, learned to play the bass, the mountain dulcimer and to sing. She started her career as a child playing with her brother in the Buck Mountain Band, and later went on to have a career in old time music playing with the likes of Whit Sizemore and the Shady Mountain Ramblers, Richard Bowman and the Slate Mountain Ramblers, banjoist and singer Larry Sigmon, The Toast String Ticklers that included Vernon Clifton, The Grayson Highland Band and others. The family legacy stayed and stays well alive.

Jennifer Bunn, Uncle Norm’s great granddaughter plays his fiddle

Today, Jimmy Edmonds still builds guitars and occasionally can be heard making one of his grandpa’s fiddles sing. Uncle Norm’s great granddaughter, Jennifer Bunn, also has one of Uncle Norm’s fiddles and plays it every chance she gets, having recorded a bluegrass CD and continues to make music in the Presbyterian Church in Hillsville that her great grandparents attended.

Next Fall, we will once again try to gather the scattered Edmonds descendants and Old Time Music fans from across the nation in my back pasture to celebrate the incredible life and legacy of Uncle Norm Edmonds. We will have folklorists, musicians and family members pay tribute to a life and legacy of old time music here in the Blue Ridge. Whatever happens, I know it will be a legacy of music and laughter.

References Used in this Article:

Bekof, J., (2012) J.P. Nester and Norman Edmonds,Old Time Party Blog, retrieved from:https://oldtimeparty.wordpress.com/2012/04/24/j-p-nestor-and-norman-edmond

Donleavy, K., (2004) Strings of Life: Conversations with Old Time Musicians from Virginia and North Carolina, Pocahontas Press, Blacksburg, VA.

Field Recorders Collective, (2015) Uncle Norm Edmond and the Old Timers,, Vols 1 and 2, (2015) 301 and 302, available at: https://fieldrecorder.bandcamp.com/album/frc-301-norman-edmonds-the-old-timers-vol-1-andy-cahan-collection

Smith, M. (2024) Personal Interview with Descendants of Norman Edmonds, September 14.

Wolfe, C.K. & Olsen, T. (Eds) (2005), The Bristol Sessions: Writings About the Big Bang of Country Music, McFarland Press, West Jefferson, NC.